Note: This post is a copy of https://paypal.gift.

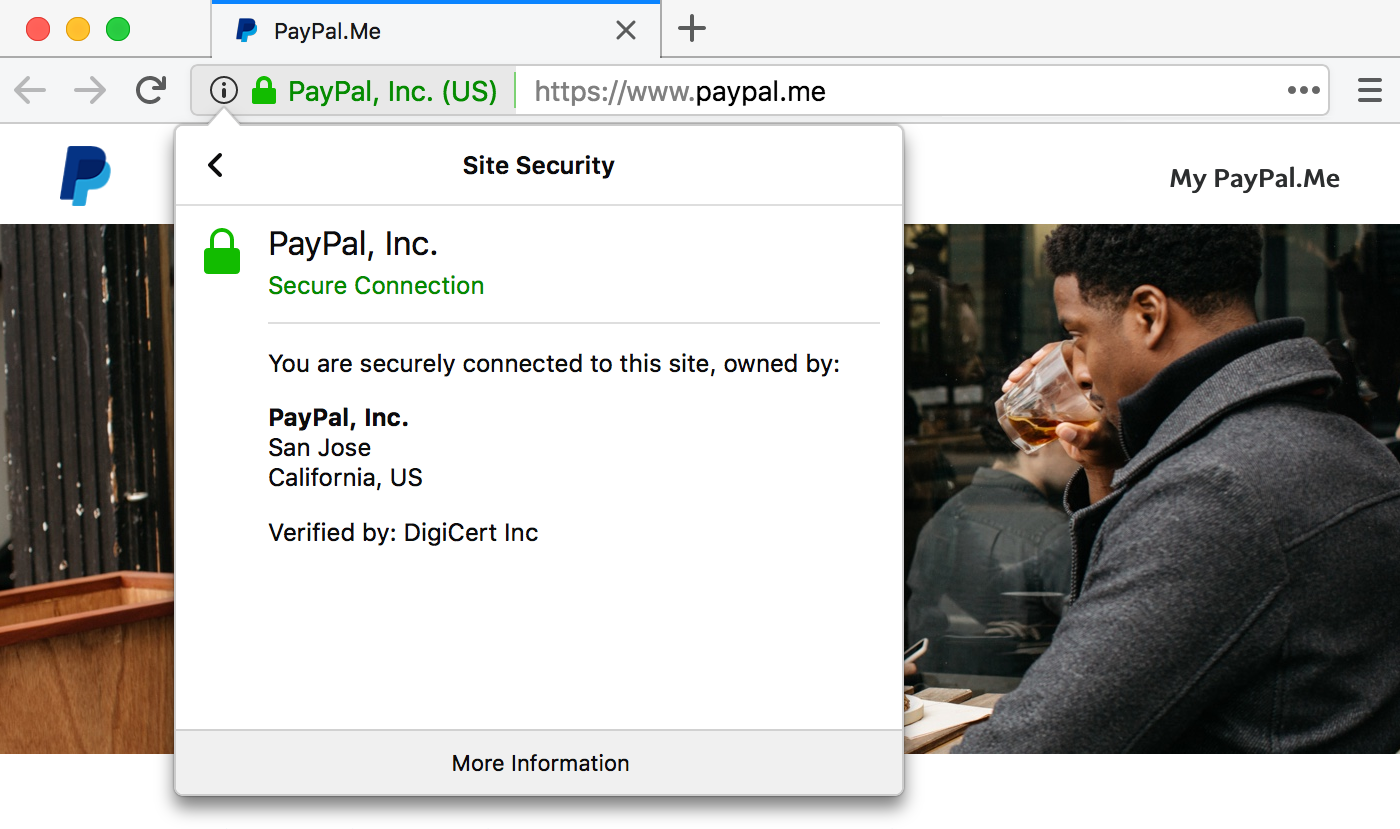

Web browsers show a padlock icon next to the URL of HTTPS websites with a valid TLS certificate. This padlock indicates that the connection between your browser and the server is secure.

It does not indicate that the website is safe to use, or that the domain name is not misleading, or anything, really. It just means that you’re connected to the address displayed in the address bar with nobody else reading or manipulating content. This type of certificate is also known as Domain Validation (“DV”) certificate and is the most common.

A different validation method called Extended Validation (“EV”) exists, where the company owning1 the domain is included in the certificate, but otherwise it’s not very different. For sites with these certificates, browsers usually show a padlock and the company name next to the URL, which can give the user a false sense of security. See Stripe, Inc and Identity Verified.

This website, paypal.gift, uses a DV certificate from Let’s Encrypt. Some people would argue that they shouldn’t have issued the certificate because the website is obviously not owned by “the real PayPal” and/or because it might be used for malicious activities. However, this is ultimately wrong because a certificate does not certify that a website is safe to use! (whatever that even means). Doing so wouldn’t be an easy task, anyway. What is a malicious site and what’s not? Who gets to decide? Is Facebook a malicious site? And if so, should they send data in plain text?

Some people still expect the CAs to do something about bad sites. Let’s Encrypt disagrees, but for a while decided to use the Google Safe Browsing API to figure out if a domain is a known bad website (by Google’s terms) before issuing a certificate. They eventually stopped doing that because it’s simply not relevant for the certificate. It would also give Google and their false positives2 the power to decide.

What Let’s Encrypt does, however, is holding a blacklist of “high value” domains3 for which they won’t automatically issue certificates until the legitimate domain owner explicitly asks them to. This is to lower the practical impact of a hostile domain takeover or BGP hijack. This blacklist includes paypal.com, but it does not include previously unregistered paypal.* domains, as I demonstrated in April 2018.4 This approach obviously does not scale and is only in place to prevent the worst, although it’s not the responsibility of the CA to prevent domain takeovers. They only validate that someone technically controls the domain.

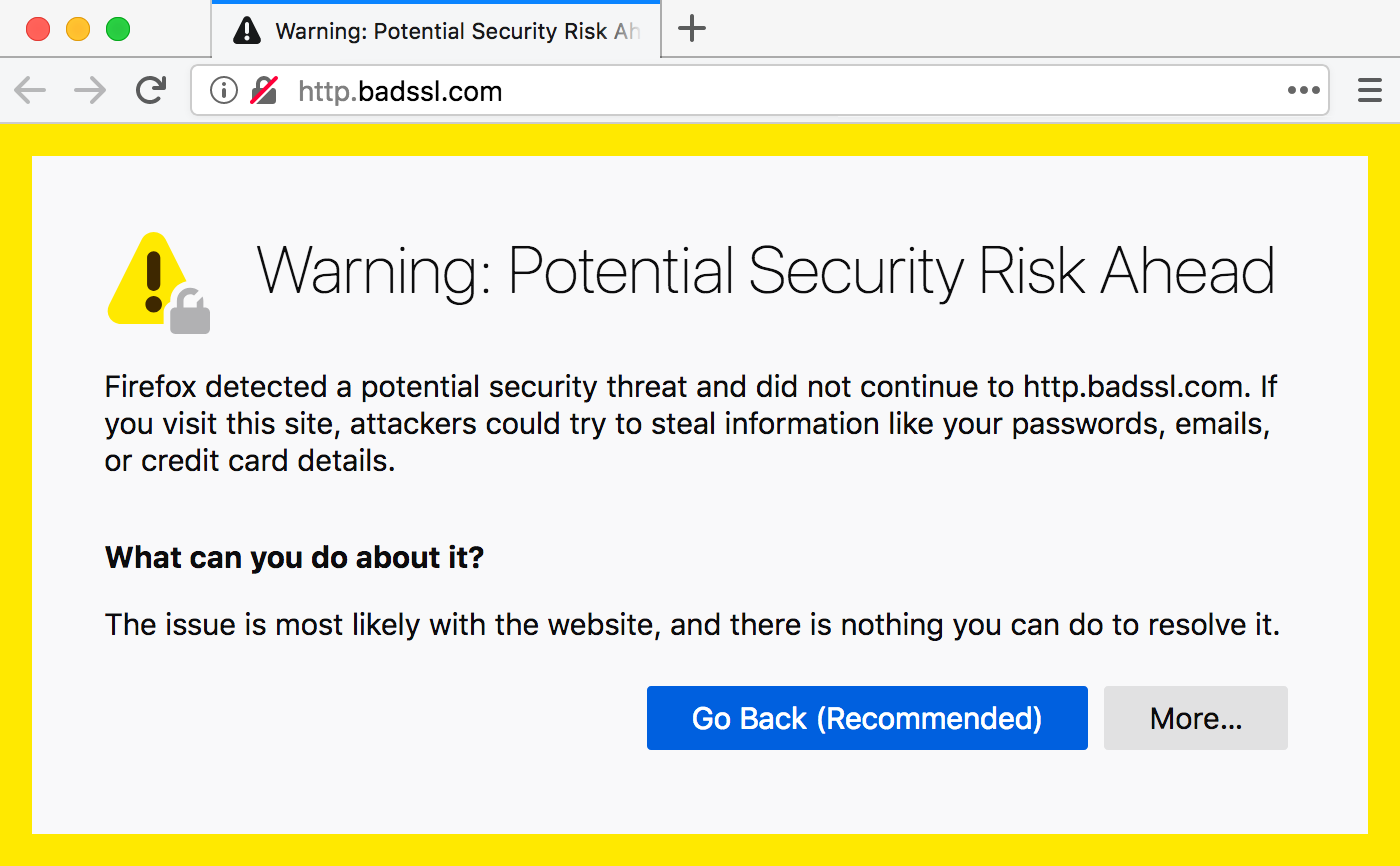

Ultimately all HTTP websites should move to HTTPS, regardless of their content, and browsers should only indicate when a connection is not secure, instead of the other way around. Padlocks and company names need to disappear. And luckily this is what’s already happening. More than ¾ of page loads now use HTTPS. Mozilla has deprecated HTTP in 2015. Firefox, Safari and Chrome are already marking some or all HTTP sites as insecure. Eventually browsers won’t connect to HTTP sites, just like sites with broken HTTPS.

-

The provided legal entity is verified to exist and to be in control of the domain in question. ↩

-

To give one recent example, Google decided that textfiles.com and all related domains are dangerous. ↩

-

Roughly Alexa Top 1000 domains and existing permutations of these domains on other TLDs. They do remove false positive permutations from the blacklist when pointed out to them. ↩

-

I acquired a certificate for paypal.cologne much to the surprise of this guy. ↩